Why working smarter is not enough

Optimal efficiency is futile if it doesn’t contribute to your goals

“Work smarter, not harder” is a staple quote in the world of business and startup inspiration porn.

At face value, I think we all can agree that this is nothing short of a solid piece of advice. After all, getting more done with less effort or fewer resources is the very definition of being efficient.

But what happens if you invest a lot of time and effort to “work smarter” on the wrong things? What if you are barking up the wrong proverbial tree?

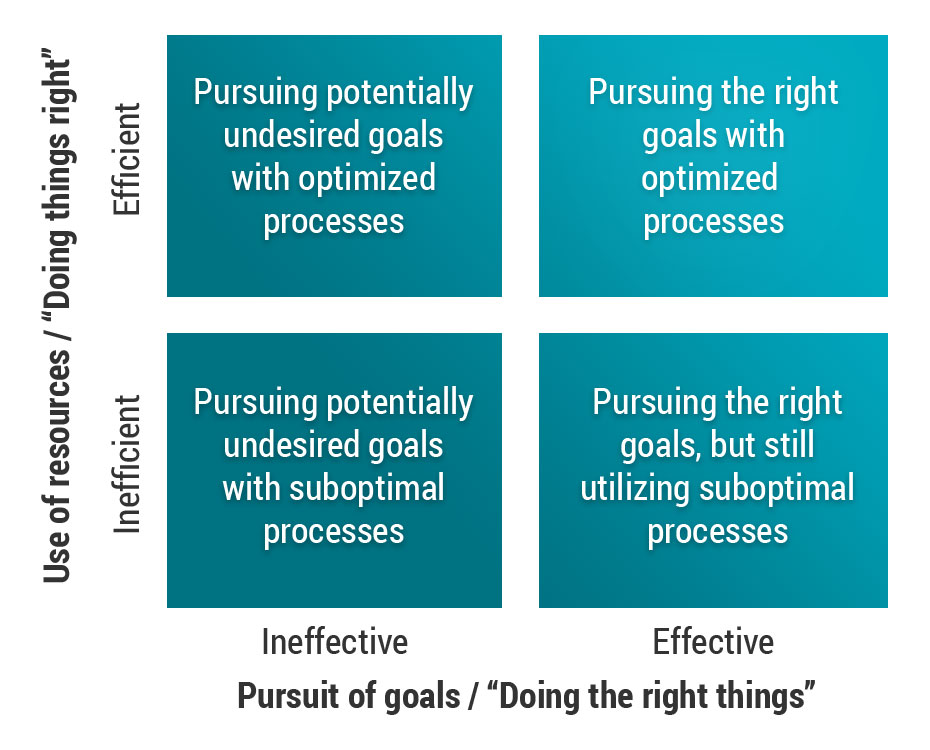

Efficiency vs. effectiveness

In my experience, it almost always pays off to be on the lookout for process optimizations, with one major caveat: it’s only worth the effort if these processes still align with the overarching business goals.

Efficiency is doing things right, while effectiveness is doing the right things.

Author Stephen R. Covey illustrates this point in his classic book The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People with the following example on the distinction between management and leadership:

Picture a group of people cutting their way through the undergrowth in a jungle with machetes, clearing the way for a new road. Among them are the managers, setting up working schedules, writing policy and procedure manuals, and making sure that the blades are kept sharp.

While the managers are busy setting up compensation programs for machete wielders to boost motivation, the leader is the one who climbs the tallest tree, peaks out above the foliage, and yells, “Wrong jungle!”

But how do the busy, efficient producers and managers often respond?

“Shut up! We’re making progress here.”

This example is by no means intended as another middle-manager bashing. Still, it puts the finger on a behavior prevalent in many of the organizations I have worked with over the past two decades:

As soon as people get financially or psychologically invested in something, biases start to appear.

And these biases have the sneaky ability to cloud their judgment. Which, inevitably, will affect their course of action in pursuing their goals. They might not even notice whether these goals are still relevant or not.

If you are working in a large organization, you might get away with going in the wrong direction for a while. But in a startup or small business with limited funds and resources, mistakes like this can be devastating. You simply cannot afford anything less than striving to be in the top right quadrant — at all times.

So — why are we so likely to continue with an investment even if it would be rational to give it up?

The Sunk Cost Fallacy

The Sunk Cost Fallacy describes our tendency to follow through on an endeavor if we have already invested time, effort, or money into it, whether or not the current costs outweigh the benefits.

In financial terms, a sunk cost is an irretrievable cost. Once spent, we cannot recover it. The fallacy occurs when we factor in those costs in our current decision-making — it is irrational to use irrecoverable costs as the rationale for making decisions in the present.

Have you ever realized halfway into watching a movie that the movie sucks, but you finished watching it anyway?

That is the sunk cost fallacy at work. The very same mechanism has been proven to impact companies and even governments.

An infamous example is the so-called Concorde Fallacy. Long before the project closed, it was clear that the financial gains of the plane would never even offset the increasing costs. Nonetheless, the project continued.

Commitment Bias

As if the Sunk Cost Fallacy wasn’t bad enough, we also have its cousin, Commitment Bias. It describes our tendency to remain committed to past decisions and behaviors — especially those involving prestige or those advocated publicly — even after it has become clear that they don’t produce the desired outcomes.

When commitment bias occurs, we feel that if we don’t stay committed, the investments we made will have all been for nothing, making us feel wasteful. Which, in turn, hampers our ability to make rational decisions.

A current example is the Agile movement’s triumphant march through the corporate world. As a business owner, senior director, or C-level executive, it’s all too easy to be seduced by the promises of constant focus on business value, shortened feedback loops, and unparalleled transparency.

And after having paid bucketloads of money for Scrum certifications, SAFe courses, and an army of Agile coaches, it can be a tough pill to swallow to realize that it just didn’t work as well as promised.

In situations like these, with personal prestige and even careers at stake, it is no wonder that people put blinders on rather than admitting that they made a bad call.

How do we know when it’s time to pull the plug?

These behaviors are hard to curb since they are so deeply rooted in our nature. It hurts to admit that we were wrong, lose face, and risk that others will think we are incompetent.

That said, becoming aware of our tendency to fall prey to these fallacies is an important first step. And instead of trying to control or ignore our emotional responses, we can turn to technology and business intelligence to help us make rational decisions.

With relevant real-time financial and operational key performance indicators in place, the numbers will bluntly reveal the state of affairs as-is — without being impacted by previous events and decisions — thus making it harder to base your conclusions on emotion.

The key here is the word “relevant.” If your KPIs measure the wrong things, you won’t get the decision basis you need.

Warning #1 — Vanity Metrics

One common problem is that some metrics, such as team productivity, throughput, and output over time, can be hard to quantify without the proper tools and processes, especially in a project- or service-oriented business.

The suggested solution to this problem is usually to find a closely related metric to the one we wanted to gauge. While this might work, you run a significant risk of measuring the map instead of the terrain — so-called vanity metrics.

For example, the productivity of software development teams is sometimes gauged by defining metrics in the application they use to report progress on their tasks. I have seen a lot of creative ideas in this department, but here are the most common ones:

- Time spent in each stage of development

- Average cycle-time from start to finish

- Total number of story points (a measure of a task’s relative complexity, as estimated by the team), a.k.a. velocity

Note that we are measuring reports about work, not the actual work performed.

It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to realize that these metrics can lead to a skewed image of reality. They fail to acknowledge delays caused by external dependencies or task statuses not updated in a timely fashion, and they are an open invitation to becoming gamed by developers and product owners alike.

Not to mention that they don’t say anything about how the work conducted correlates with its business value as perceived by the client.

Warning #2 — Confirmation Bias and Obstruction

Yep, another bias. As the name suggests, we people are suckers for getting our beliefs and preconceptions validated.

People’s opinions will affect their actions and decisions, which might result in obstruction and all-out activism against unpopular changes in strategy and operations.

As a leader, you need to be aware of this when you evaluate the decision basis — not only regarding your own biases but also those of anyone involved in the reporting chain.

In conclusion

Effectiveness trumps efficiency. Doing the right things is more important than doing things right. Make a habit of asking, “Why are we doing this?” and if it doesn’t add value to your customers, it’s not worth doing.

Use technology to get accurate, real-time business intelligence, but don’t indulge in vanity metrics.

Make all hours count—track time to learn where there are productivity optimization opportunities and to get better at estimating, but don’t create an Orwellian surveillance state.

Focus on goals and output, and create a culture where it’s encouraged to challenge the status quo.

Work harder on identifying and implementing the processes that align with your long-term business strategy — then work smarter.